So, unfortunately, going on vacation kind of threw a wrench in my plans to do full reviews of the last book in the Old Man's War series, The Last Colony, and its two offshoots, The Sagan Diary and Zoe's Tale, so I am going to toss out a few thoughts I had about them here in lieu of a full review, and hopefully get back to complete reviews of other books soon.

The Last Colony is a great ending to the Old Man's War trilogy. It picks up eight years after the events of The Ghost Brigades, and is told once again from the perspective of John Perry, who has been living a quiet, happy life on an established colony with his wife, Jane Sagan, and their adopted daughter, Zoe Boutin-Perry. Then, one day, the Colonial Union shows up at his door and asks if he and his family will relocate and become the leaders of a new colony that is going to be populated not by people from Earth, as all previous colonies have been, but by people hand-selected from ten different colony worlds. It's an experiment in colony cooperation, and something the colonists on those worlds have been pushing for for a long time, they say, and the colony is to be called Roanoke.

Now if you, like me, are asking yourself why anyone would name a colony Roanoke, or why anyone would agree to become part of a colony called Roanoke, the reason for its name becomes clear quickly enough, but I won't say much more about it so as not to give any significant plot points away. This story does as good a job at unpacking the logistics behind colonization and interstellar politics as the other two books did with warfare and the use of advanced technology, and it has an ending that I found unexpected, but that wraps everything up in such a way that once you look back, you realize that the story couldn't have ended any other way. If you read and liked Old Man's War and The Ghost Brigades, you couldn't ask for a better ending to that story than The Last Colony.

The Sagan Diary is a short story that takes place on the heels of The Ghost Brigades, and is told in first-person perspective as a series of diary entries from Jane Sagan to John Perry just before she is planning on leaving the Ghost Brigades to live a normal, human life with him and Zoe. There's not much that I can say about this story; it's a good philosophical study, and an interesting look into the character's mind, but it has no plot and no storyline of its own. A good companion read to the other books, but can't really stand on its own.

Zoe's Tale, on the other hand, is a fascinating return to the world of Old Man's War, because it tells the story of The Last Colony from the perspective of John and Jane's daughter, Zoe. If you read through The Last Colony and find some things lacking, or feel that a very specific climax within the book is resolved too easily, then you definitely need to read Zoe's Tale as well. It also does an amazing job of capturing the voice and personality of a teenage girl, which I have to applaude John Scalzi for. He states in the acknowledgements that this was accomplished not by hanging out with teenage girls, as one of his male friends had unhelpfully suggested, but by reaching out to women he knew and trusted and asking their opinions and advice.

This is something that I feel both male and female writers can learn from when trying to write stories containing characters of the opposite gender (and, ideally, most well-written stories should contain both male and female characters). Writers of both genders, especially in genre fiction, tend to fall back on stereotypes or caricatures when characters of the opposite gender, which can be easier than acknowledging that you don't really know how to place yourself inside the head of a person who does not share your gender, but is all-too-obvious to the reader that shares that character's gender. It is Zoe's realistic and recognizable personality that makes Zoe's Tale my favorite of all the books in the Old Man's War series, and it is well worth reading all of the others to read this one at the last.

The Last Colony, by John Scalzi

The Sagan Diary, by John Scalzi

Zoe's Tale, by John Scalzi

Sunday, October 7, 2012

Sunday, August 19, 2012

A Second Book, Better Than the First: The Ghost Brigades, by John Scalzi

(Author's Note: This review will contain major spoilers for Old Man's War, so if you are planning on reading that book and don't want to know about what happens in it beforehand, hold off on reading this review. Thanks. - SW)

Though I don't think I said it specifically in my previous review, the best thing I liked about Old Man's War was the universe that it created: a universe full of everything that I both hope for and fear about a science fiction future, based on some of the best modern science I've ever seen used in a sci-fi novel. The best thing about its sequel, The Ghost Brigades, is that it expands that universe in ways that are unexpected, brilliant, and totally in keeping with my expectations for how the universe and the technology it revolves around would advance.

In Old Man's War, we see everything through the eyes of John Perry, a seventy-five-year-old man recruited from Earth to be given a new life as a super-soldier out in a galaxy fraught with war. We see the technology and the aliens and the politics he is introduced to through his eyes, giving us as good an introduction to the way things are as he gets. He does receive a slightly broader perspective than his fellow soldiers, though, when he discovers the existence of the Ghost Brigades, another group of super-soldiers that are cloned from the DNA of volunteers for the CDF that die before they can enlist. Specifically, he meets a woman named Jane Sagan who was cloned from his wife's DNA, and from her he learns a little about what it is like to be born as a fully-grown adult human, with a head full of knowledge but no memories, and how being bred to do nothing but fight can give one a very different perspective on life.

In The Ghost Brigades, though it is told from the point of view of more than one person, we finally get a first-hand look into the mind and experiences of a Ghost Brigade soldier. The story starts with Jane Sagan discovering an alliance that has been made between three alien races--the Rraey (the aliens who attacked Coral in the previous book), the Eneshans, and the Obin--who are planning on making war against the Colonial Union with the help of a human defector, a scientist named Charles Boutin. Everyone had thought that he had committed suicide, but he had actually just murdered a clone of himself before fleeing. Unfortunately, in his haste, he left a copy of a brain-scan he had done on himself behind, so the CDF, with the help of the Ghost Brigades, decides to clone him again and see if they can transfer his brain patterns into the new body in order to find out why he had defected and what information he was planning on giving their enemies. Things don't exactly go as planned, though, so they end up instead with a Ghost Brigade soldier, who is given the name Jared Dirac, and then we get to see the process by which someone becomes a Ghost Brigade soldier the same way that we saw John Perry become a CDF soldier before the story jumps off into the deep waters of the plot.

Throughout this book, Scalzi addresses the use of computer-brain interfacing in a way that is both well-researched and well-balanced, and, as with his first book, he uses likely end-results of technology that we already have or are working towards as a jumping-off point for larger discussions about politics, culture, intelligence, self-awareness, autonomy, and even the meaning of consciousness itself. And yet, there is never anything preachy about the narrative. The brilliance of telling these stories from individual points of view, even when doing so through multiple character perspectives within a book, is that it allows you to get each person's private thoughts and opinions on the events and draw your own conclusions based on your own thoughts and experiences with the same ideas. I love books that make me think without telling me what to think, and few books have ever made me think quite as much as this one did.

It is also one of the first times I have ever seen the discussion of the separation of intelligence and consciousness so brilliantly illustrated. Without giving too much away (I hope), I will say that it is discovered over the course of this book that the Obin are an uplifted species: the Consu (the super-advanced aliens from the first book whose motives for warfare with all the other species in the galaxy are inscrutable and vaguely religious) gave them intelligence at some point in their past, possibly as some sort of experiment. What they didn't give them, though, was consciousness. They can think, and reason, and understand, and create and use technology as well as any sentient species in the galaxy, but they have no higher emotions; they cannot love, or hate, or fear, or grieve. They have no culture, no ambition, and no desires except one--as a species, they know they lack true consciousness, and will do anything they need to in order to find a way to obtain it for themselves.

The Obin are almost the perfect way of explaining the difference between humans and animals who exhibit levels of intelligence that are very similar to ours. We know now that there are many highly-intelligent species of animals, but what all humans have that animals lack is consciousness--the ability to feel emotions based on our understanding of our past, future, mortality, and awareness of the world around us. And by bringing both the Obin and the soldiers of the Ghost Brigade together in this story, Scalzi delves deep into the realm of philosophy and brings modern science along for the ride. And this is only the second book of a trilogy! I can't wait to see what he does with the last one. :)

The Ghost Brigades, by John Scalzi

Though I don't think I said it specifically in my previous review, the best thing I liked about Old Man's War was the universe that it created: a universe full of everything that I both hope for and fear about a science fiction future, based on some of the best modern science I've ever seen used in a sci-fi novel. The best thing about its sequel, The Ghost Brigades, is that it expands that universe in ways that are unexpected, brilliant, and totally in keeping with my expectations for how the universe and the technology it revolves around would advance.

In Old Man's War, we see everything through the eyes of John Perry, a seventy-five-year-old man recruited from Earth to be given a new life as a super-soldier out in a galaxy fraught with war. We see the technology and the aliens and the politics he is introduced to through his eyes, giving us as good an introduction to the way things are as he gets. He does receive a slightly broader perspective than his fellow soldiers, though, when he discovers the existence of the Ghost Brigades, another group of super-soldiers that are cloned from the DNA of volunteers for the CDF that die before they can enlist. Specifically, he meets a woman named Jane Sagan who was cloned from his wife's DNA, and from her he learns a little about what it is like to be born as a fully-grown adult human, with a head full of knowledge but no memories, and how being bred to do nothing but fight can give one a very different perspective on life.

In The Ghost Brigades, though it is told from the point of view of more than one person, we finally get a first-hand look into the mind and experiences of a Ghost Brigade soldier. The story starts with Jane Sagan discovering an alliance that has been made between three alien races--the Rraey (the aliens who attacked Coral in the previous book), the Eneshans, and the Obin--who are planning on making war against the Colonial Union with the help of a human defector, a scientist named Charles Boutin. Everyone had thought that he had committed suicide, but he had actually just murdered a clone of himself before fleeing. Unfortunately, in his haste, he left a copy of a brain-scan he had done on himself behind, so the CDF, with the help of the Ghost Brigades, decides to clone him again and see if they can transfer his brain patterns into the new body in order to find out why he had defected and what information he was planning on giving their enemies. Things don't exactly go as planned, though, so they end up instead with a Ghost Brigade soldier, who is given the name Jared Dirac, and then we get to see the process by which someone becomes a Ghost Brigade soldier the same way that we saw John Perry become a CDF soldier before the story jumps off into the deep waters of the plot.

Throughout this book, Scalzi addresses the use of computer-brain interfacing in a way that is both well-researched and well-balanced, and, as with his first book, he uses likely end-results of technology that we already have or are working towards as a jumping-off point for larger discussions about politics, culture, intelligence, self-awareness, autonomy, and even the meaning of consciousness itself. And yet, there is never anything preachy about the narrative. The brilliance of telling these stories from individual points of view, even when doing so through multiple character perspectives within a book, is that it allows you to get each person's private thoughts and opinions on the events and draw your own conclusions based on your own thoughts and experiences with the same ideas. I love books that make me think without telling me what to think, and few books have ever made me think quite as much as this one did.

It is also one of the first times I have ever seen the discussion of the separation of intelligence and consciousness so brilliantly illustrated. Without giving too much away (I hope), I will say that it is discovered over the course of this book that the Obin are an uplifted species: the Consu (the super-advanced aliens from the first book whose motives for warfare with all the other species in the galaxy are inscrutable and vaguely religious) gave them intelligence at some point in their past, possibly as some sort of experiment. What they didn't give them, though, was consciousness. They can think, and reason, and understand, and create and use technology as well as any sentient species in the galaxy, but they have no higher emotions; they cannot love, or hate, or fear, or grieve. They have no culture, no ambition, and no desires except one--as a species, they know they lack true consciousness, and will do anything they need to in order to find a way to obtain it for themselves.

The Obin are almost the perfect way of explaining the difference between humans and animals who exhibit levels of intelligence that are very similar to ours. We know now that there are many highly-intelligent species of animals, but what all humans have that animals lack is consciousness--the ability to feel emotions based on our understanding of our past, future, mortality, and awareness of the world around us. And by bringing both the Obin and the soldiers of the Ghost Brigade together in this story, Scalzi delves deep into the realm of philosophy and brings modern science along for the ride. And this is only the second book of a trilogy! I can't wait to see what he does with the last one. :)

The Ghost Brigades, by John Scalzi

Sunday, August 5, 2012

Now This is Good Sci-Fi: Old Man's War, by John Scalzi

I'm almost ashamed that it's taken me this long to read anything by John Scalzi. I am a fan of science fiction, but my knowledge of the genre barely skims the surface, and focuses more on the realm of television sci-fi rather than written. But if there was ever a good place to start with modern science fiction, this is it.

In Old Man's War, though the galaxy of our future has space travel and aliens and hundreds of habitable planets all across the universe, Earth is essentially cut off from all of it. Its connection the to rest of the universe is carefully controlled by an organization called the Colonial Union. They control the only means of getting off-planet, and when a person leaves Earth, either to become a colonist or to join the Colonial Defense Forces, they are never allowed to return. Colonists are chosen from countries that were nuked during Earth's last great war and can now no longer support their populations, and soldiers are chosen from the planet's elderly. On a person's seventy-fifth birthday, they can choose to be declared legally dead, taken off-planet forever, and somehow turned into a soldier. Everyone on Earth wonders what military could want people who are almost at the end of their lives, and, more importantly, do they have some way to reverse the aging process, to make old bodies young again?

The book's protagonist, John Perry, walks into his local recruitment office on his seventy-fifth birthday with nothing left to lose. He and his wife had decided ten years ago to both join up, but then she died of a stroke. He's not particularly close to his son, and he sees nothing ahead of him except the inevitable betrayal and breakdown of his body if he stays on Earth, so he'd rather take his chances with the military. His voice is really what makes the story: he confronts all the strangeness that he finds out in the galaxy with pragmatism, logic, and a sense of humor that are completely relatable and very fun to read. There were a few sections, especially near the beginning, that had me laughing out loud (when you read it, you will totally know which parts I'm talking about too), and I could relate to his opinions and feelings about pretty much everything, which is less common even in the books than I love than you might imagine.

All of these things make Old Man's War a great book, but it's what makes it great science fiction that really hooked me. Our understanding of, for lack of a better term, the "science of the future" has expanded a lot over the last decade or so, so much so that a lot of the science fiction that I loved before this required a significant amount of suspension of disbelief as far as the technology was concerned. Things like teleporters, warp drive, humanoid aliens, and ray-guns are easy and recognizable tropes, but they are no longer based in science as we currently understand it. As a lover of modern science and technology and all the things it does promise us, Scalzi's take on the future was something I could believe in. It used quantum physics, modern computer technology, and everyone's hopes for the Singularity to create a future for humanity that, while not necessarily desirable, is as least possible, for better and for worse.

My only complaint about the novel itself was that I felt it ended too soon. The first two-thirds of the book was full of amazing, fast-paced exposition and brilliant descriptions that immersed me completely in the story's universe. Then, several major events happen, all of which felt like they wrapped up way too fast, and suddenly it was all over. Lucky for me, though, there are several sequels, which I will be reading and reviewing in very short order, and which will hopefully be just as amazing as this one was.

Reading Old Man's War also revealed something about how I've evolved in thinking of myself as a writer that I hadn't expected. When I put the book down after reading the last word, my first thought was, "I'll never be as good a writer as he is,"but my second thought was, "All the more reason to keep trying." At some point over the last few months, I've turned a corner in my own hopes for my future as an author, and the fact that I can read someone else's work and see something to strive for in it rather than something unattainable is one of the best places I could hope to be at this point.

Old Man's War, by John Scalzi

As a final note, here are two essays written by John Scalzi that I ran across in recent weeks and were one of the reasons why I decided to give his novels a shot. I've started following his blog, and he's well on his way to becoming one of my favorite authors.

http://whatever.scalzi.com/2012/07/26/who-gets-to-be-a-geek-anyone-who-wants-to-be/

http://whatever.scalzi.com/2012/07/23/a-self-made-man-looks-at-how-he-made-it/

In Old Man's War, though the galaxy of our future has space travel and aliens and hundreds of habitable planets all across the universe, Earth is essentially cut off from all of it. Its connection the to rest of the universe is carefully controlled by an organization called the Colonial Union. They control the only means of getting off-planet, and when a person leaves Earth, either to become a colonist or to join the Colonial Defense Forces, they are never allowed to return. Colonists are chosen from countries that were nuked during Earth's last great war and can now no longer support their populations, and soldiers are chosen from the planet's elderly. On a person's seventy-fifth birthday, they can choose to be declared legally dead, taken off-planet forever, and somehow turned into a soldier. Everyone on Earth wonders what military could want people who are almost at the end of their lives, and, more importantly, do they have some way to reverse the aging process, to make old bodies young again?

The book's protagonist, John Perry, walks into his local recruitment office on his seventy-fifth birthday with nothing left to lose. He and his wife had decided ten years ago to both join up, but then she died of a stroke. He's not particularly close to his son, and he sees nothing ahead of him except the inevitable betrayal and breakdown of his body if he stays on Earth, so he'd rather take his chances with the military. His voice is really what makes the story: he confronts all the strangeness that he finds out in the galaxy with pragmatism, logic, and a sense of humor that are completely relatable and very fun to read. There were a few sections, especially near the beginning, that had me laughing out loud (when you read it, you will totally know which parts I'm talking about too), and I could relate to his opinions and feelings about pretty much everything, which is less common even in the books than I love than you might imagine.

All of these things make Old Man's War a great book, but it's what makes it great science fiction that really hooked me. Our understanding of, for lack of a better term, the "science of the future" has expanded a lot over the last decade or so, so much so that a lot of the science fiction that I loved before this required a significant amount of suspension of disbelief as far as the technology was concerned. Things like teleporters, warp drive, humanoid aliens, and ray-guns are easy and recognizable tropes, but they are no longer based in science as we currently understand it. As a lover of modern science and technology and all the things it does promise us, Scalzi's take on the future was something I could believe in. It used quantum physics, modern computer technology, and everyone's hopes for the Singularity to create a future for humanity that, while not necessarily desirable, is as least possible, for better and for worse.

My only complaint about the novel itself was that I felt it ended too soon. The first two-thirds of the book was full of amazing, fast-paced exposition and brilliant descriptions that immersed me completely in the story's universe. Then, several major events happen, all of which felt like they wrapped up way too fast, and suddenly it was all over. Lucky for me, though, there are several sequels, which I will be reading and reviewing in very short order, and which will hopefully be just as amazing as this one was.

Reading Old Man's War also revealed something about how I've evolved in thinking of myself as a writer that I hadn't expected. When I put the book down after reading the last word, my first thought was, "I'll never be as good a writer as he is,"but my second thought was, "All the more reason to keep trying." At some point over the last few months, I've turned a corner in my own hopes for my future as an author, and the fact that I can read someone else's work and see something to strive for in it rather than something unattainable is one of the best places I could hope to be at this point.

Old Man's War, by John Scalzi

As a final note, here are two essays written by John Scalzi that I ran across in recent weeks and were one of the reasons why I decided to give his novels a shot. I've started following his blog, and he's well on his way to becoming one of my favorite authors.

http://whatever.scalzi.com/2012/07/26/who-gets-to-be-a-geek-anyone-who-wants-to-be/

http://whatever.scalzi.com/2012/07/23/a-self-made-man-looks-at-how-he-made-it/

Sunday, July 29, 2012

Some Short Fiction

No new book review this week, but I'm trying to get back into posting regularly, so I figured I'd share a couple of short fiction stories that I've written recently.

The first is a piece based on my experience playing the video game Skyrim. I find certain video games to be a great source of creative inspiration because the setting is already there for me to wander through and the events that effect my character's life have been pre-scripted, but the character herself is a blank slate that I can imprint thoughts, feelings, and a personality onto. This first story is told from the perspective of my character in Skyrim right before and right after the game's final battle. It hopefully expresses both my pride at getting as far as I had and at accomplishing so much, and also the frustration that I felt at the fact that the game had no real ending--just a stopping point, chosen by me when I decided that I had gotten all I could out of the experience. Enjoy!

Efran instinctively shied away from the ragged young woman stinking of poverty that had emerged from the dark alley and was now approaching him. Her back was bent subserviently, but her lowered eyes kept flickering up at his face, full of greed and expectation. As she came closer, he pulled his uniform jacket back to reveal the holster concealed at his hip and placed a hand on the pistol’s grip. “Begone, woman. Peddle your filth elsewhere.” With a squeak of fear, she retreated back the way she had come, and he continued down the street, unmolested by the other street scum littering the nearby alleys and doorways.

He didn’t understand the appeal of emotions, anyway. His people had discarded such things in their distant evolutionary past, and until the Fleet had encountered humans, they had considered it no great loss. But then they had brought this one, seemingly-insignificant planet into the Empire, and, suddenly, the damn things were everywhere. It had taken less than a decade for human scientists to discover that certain natural compounds, when injected or ingested by his people, could simulate the emotions that so many alien cultures in the Empire took for granted. Of course, the Generals had immediately made the creation, sale, and use of such unnatural drugs illegal, but that hadn’t stopped them from taking over his people like an epidemic.

Even Tama, his partner, hadn’t been immune to the siren call of the ‘feelies.’ After the loss of their second clutch to one of the many diseases that ran rampant through the population of this vile, disgusting world, a friend of hers had introduced her to ‘happiness’ in an effort to encourage her to try again. She had quickly become addicted, to ‘happiness’ and to many of the other emotions that were sold on the black market. She had gone to ‘sadness’ as a way to express the effect that the loss of her potential children had had on her, to ‘anger’ when he didn’t take her ‘feelings’ seriously, to ‘despair’ when he could not be persuaded by her incomprehensible arguments, and had finally lost herself in ‘bliss’ and had wasted away. The last time Efran had seen her, she was a hollow shell of herself, her eyes that had once been so full of intelligence and curiosity about the world blank and glazed from the effects of the drug. She was in a hospital somewhere now, and as soon as her addiction to the drug was severed, she would be sent back to the homeworld, never to leave it again. And since he, as a soldier of the Fleet, had severed all ties to that place, he would never see it, or her, again.

After his patrol that evening, as he sat alone in his quarters in the barracks, Efran thought back to Tama and to all the other friends and fellow soldiers that he had lost to the ‘feelies’ since coming to this planet. What did they see in being so crippled by chemicals that they were no longer able to think or act rationally? Couldn’t they see that it was emotion that had held all of the aliens that were now under control of the Empire back, that had allowed them to be subjugated by the fleet? That woman today… who knows what she could have been, what heights she and her fellow humans could have reached if they had not been slaves to things like ‘fear’ and ‘uncertainty’?

Suddenly, there was a blinding flash of light, and the far wall of his room exploded. The next thing Efran knew, he was being pulled out of the rubble of the barracks by a medic. “Suicide bomber,” the medic explained as he applied bandages to deep cuts on Efran’s leg, arm, and head. “These humans are all insane. Any word on how much longer we’re planning on trying to hold on to this worthless ball of rock, sir?”

Efran nodded vaguely as he looked around at the dead bodies littering the ground. Over half his squad, dead in an instant, all because of these humans and their emotions. Sometimes it was enough to make him…

Late that night, long after curfew, Efran found himself back on the street he had patrolled that morning, standing in the mouth of a filthy, stinking alley. The woman was still there, huddled in a bundle of rags behind an overflowing dumpster. She looked up at him, terrified, but also hopeful.

“Rage, please,” was all he had to say.

The first is a piece based on my experience playing the video game Skyrim. I find certain video games to be a great source of creative inspiration because the setting is already there for me to wander through and the events that effect my character's life have been pre-scripted, but the character herself is a blank slate that I can imprint thoughts, feelings, and a personality onto. This first story is told from the perspective of my character in Skyrim right before and right after the game's final battle. It hopefully expresses both my pride at getting as far as I had and at accomplishing so much, and also the frustration that I felt at the fact that the game had no real ending--just a stopping point, chosen by me when I decided that I had gotten all I could out of the experience. Enjoy!

So this is what it finally comes to.

I came into this country less than a year ago as a prisoner awaiting execution, with no memory of who I was, where I had come from, or what I had done to deserve my fate; no memories at all except for my name. And then a dragon attacked.

That attack saved my life, though I’m not entirely sure that was what the dragon had had in mind, because ever since then I can’t seem to go anywhere without being attacked by dragons. I know why that is now—it’s because I’m Dragonborn. I can speak with the voice of the dragons, and it is my destiny to kill the dragon that inadvertently saved my life in order to prevent the end of the world.

If I had been smart, I would have left Skyrim as soon as I found out, but there were two problems with that plan. Firstly, I don’t think it would have actually helped—prophecy and destiny aren’t usually things you can run away from, and the last thing I want is to be responsible for the end of the world. And secondly, Skyrim has become my home. I didn’t mean for it to happen, but somewhere along the way, between surviving and trying to discover who I am, I made a home and a future for myself here. I made friends and companions, helped a lot of people, and even secured Skyrim’s future as a free and independent nation. It no longer matters to me that I don’t have a past, because I made a present and a future for myself here, and that is something worth sticking around and fighting for.

So I stand here now on the edge of the abyss in my armor made of the bones of the dragons I have slain, the blade of my war-axe crimson with the blood of fallen foes, thinking about what little past I have even as I wonder if I will have a future once I step into that pillar of fire. I may not have spent very long in this land, but I have left my mark. Elshara Dovhakin is the leader of the Companions, Listener for the Dark Brotherhood, savior of the Riften thieves’ guild, Archmage of the College of Winterhold, and Thane of Whiterun. I am the hero of the Stormcloak rebellion. I assassinated the emperor of Tamriel. I have faced down Daedric Lords, discovered lost empires, saved tiny hamlets and large cities alike from dragons, and have slain every beast, monster, and enemy that has wanted me dead. And now I must enter Sovngarde, the Nordic realm of the dead, and kill Alduin, the most powerful dragon in all of Tamriel, the dragon whose coming foretells the end of the world.

How hard could it be?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

It is done.

The battle was long and hard-fought, but with the souls of Skyrim’s greatest heroes standing beside me, we managed to win the day. Alduin World-Ender is now well and truly slain. He will never trouble the lands of the living or the dead again, and without him to resurrect them and give them power, the rest of the dragons that have been plaguing Skyrim will soon fade into obscurity and legend again. And now I hope to do the same.

I sit now in my home in Windhelm, watching the ever-present snow falling outside the window. I have hung up my axe and my armor, stored away all of my adventuring gear, and have stocked my kitchen pantry for the very first time. I sent Lydia, my housecarl, back to my house in Whiterun to look after my interests there for a while. The house is blessedly quiet and peaceful, and I’m looking forward to staying awhile, to sleeping in a bed and eating decent food and not getting attacked by enemies everywhere I go. My adventuring days aren’t over, and probably never will be, but I just saved the world, so I think I deserve a rest.

Was that a knock on the door?

The second story was inspired by a writing prompt from one of my favorite websites, io9.com, which runs a weekly series called the Concept Art Writing Prompt. Every Saturday, they find a piece of random science-fiction or fantasy inspired artwork on the web and invite their readers to write short works of fiction based on them. In this piece, I use the idea of bottled emotions to try my hand at true science-fiction for the first time

“Hey there, soldier, wanna buy a feelie?”

Efran instinctively shied away from the ragged young woman stinking of poverty that had emerged from the dark alley and was now approaching him. Her back was bent subserviently, but her lowered eyes kept flickering up at his face, full of greed and expectation. As she came closer, he pulled his uniform jacket back to reveal the holster concealed at his hip and placed a hand on the pistol’s grip. “Begone, woman. Peddle your filth elsewhere.” With a squeak of fear, she retreated back the way she had come, and he continued down the street, unmolested by the other street scum littering the nearby alleys and doorways.

He didn’t understand the appeal of emotions, anyway. His people had discarded such things in their distant evolutionary past, and until the Fleet had encountered humans, they had considered it no great loss. But then they had brought this one, seemingly-insignificant planet into the Empire, and, suddenly, the damn things were everywhere. It had taken less than a decade for human scientists to discover that certain natural compounds, when injected or ingested by his people, could simulate the emotions that so many alien cultures in the Empire took for granted. Of course, the Generals had immediately made the creation, sale, and use of such unnatural drugs illegal, but that hadn’t stopped them from taking over his people like an epidemic.

Even Tama, his partner, hadn’t been immune to the siren call of the ‘feelies.’ After the loss of their second clutch to one of the many diseases that ran rampant through the population of this vile, disgusting world, a friend of hers had introduced her to ‘happiness’ in an effort to encourage her to try again. She had quickly become addicted, to ‘happiness’ and to many of the other emotions that were sold on the black market. She had gone to ‘sadness’ as a way to express the effect that the loss of her potential children had had on her, to ‘anger’ when he didn’t take her ‘feelings’ seriously, to ‘despair’ when he could not be persuaded by her incomprehensible arguments, and had finally lost herself in ‘bliss’ and had wasted away. The last time Efran had seen her, she was a hollow shell of herself, her eyes that had once been so full of intelligence and curiosity about the world blank and glazed from the effects of the drug. She was in a hospital somewhere now, and as soon as her addiction to the drug was severed, she would be sent back to the homeworld, never to leave it again. And since he, as a soldier of the Fleet, had severed all ties to that place, he would never see it, or her, again.

After his patrol that evening, as he sat alone in his quarters in the barracks, Efran thought back to Tama and to all the other friends and fellow soldiers that he had lost to the ‘feelies’ since coming to this planet. What did they see in being so crippled by chemicals that they were no longer able to think or act rationally? Couldn’t they see that it was emotion that had held all of the aliens that were now under control of the Empire back, that had allowed them to be subjugated by the fleet? That woman today… who knows what she could have been, what heights she and her fellow humans could have reached if they had not been slaves to things like ‘fear’ and ‘uncertainty’?

Suddenly, there was a blinding flash of light, and the far wall of his room exploded. The next thing Efran knew, he was being pulled out of the rubble of the barracks by a medic. “Suicide bomber,” the medic explained as he applied bandages to deep cuts on Efran’s leg, arm, and head. “These humans are all insane. Any word on how much longer we’re planning on trying to hold on to this worthless ball of rock, sir?”

Efran nodded vaguely as he looked around at the dead bodies littering the ground. Over half his squad, dead in an instant, all because of these humans and their emotions. Sometimes it was enough to make him…

Late that night, long after curfew, Efran found himself back on the street he had patrolled that morning, standing in the mouth of a filthy, stinking alley. The woman was still there, huddled in a bundle of rags behind an overflowing dumpster. She looked up at him, terrified, but also hopeful.

“Rage, please,” was all he had to say.

Sunday, July 22, 2012

Two Reviews in One... One Good, One Bad: Wicked, by Gregory Maguire

I can't tell you how badly I wanted to like this book. It was a present from someone several years ago, a book that I started reading at one point and then never went back to for reasons that I could not remember until I picked it up again. And then, a month ago, I finally got to see the Broadway musical version of Wicked, and I was blown away. Not just by the music, or the experience of going to the theater, which are what I usually remember about such experiences, but by the story, and the characters, and the drama wrapped in humor with a very liberal sprinkling of political commentary. It was one of those stories that I know will stick with me for a very long time, and given that it wasn't an experience that I could easily go back and have again, I couldn't wait to relive the story and its characters in their original form. It was time to give Wicked, the book, another chance.

And that was the only reason why I pressed on through the novel long past the time I would have normally put it down: the hope that somewhere out of the mess of complicated language, unlikeable characters, and incomprehensible plot would come some glimmer of the story that I had fallen in love with. Unfortunately, it was nowhere to be found. The musical took the basic premise--tell the story behind the Wicked Witch of the West--and its broadest brushstrokes--character names, the general tone of their relationships to one another, and some of the events in their lives that play a part in their motivations--but other than that, the two stories could not be more different.

In Wicked, the novel, Elphaba, the green-skinned girl who eventually grows up to become the Wicked Witch of the West, is a strange, wholly-unlikeable person. She doesn't know how to relate to anyone, her motivations are never truly made clear, and the only thing that makes her a remotely sympathetic character is the fact that she seems completely oblivious as to how to do anything to make people like her. That would not be enough to completely derail the story--unlikeable characters can often be made sympathetic through the adversity they face and the people that they face them with--except that there is not a single other character in this novel that is any more likable, accessible, or understandable. I am willing to believe that there was some deep political commentary going on within the novel, but the author's descriptive language was so complicated, the character's dialogue so flowery and actions so incomprehensible, and the flow of the plot so random-seeming that it was impossible for me to concentrate on anything other than getting to the next chapter in the hopes that the story would become what I had been expecting it to be. Unfortunately, it never did.

Which is sad, because the story told by Wicked, the musical, is one that I would have loved to read. In the musical, Elphaba is a likable by introverted girl who has been shunned and hated by everyone simply because she was born with green skin and an innate talent for magic that no one had ever seen before. When she goes to Shiz, Oz's university, she is initially treated to levels of ridicule and scorn that any girl, but especially a nerdy, introverted girl, can sympathize with. To make matters worse, she is forced to room with the most popular girl in the school, Galinda, and the two become instant enemies. Over time, though, that enmity transforms into respect, which then blossoms into a friendship between the two young women that is as strong and realistic and relatable as the two characters themselves are. Though they go their separate ways over an event that leads to Elphaba becoming known throughout Oz as the Wicked Witch and Galinda becoming Glinda the Good Witch, they still remain friends, and this colors all of the events that follow the story of The Wizard of Oz in an entirely different light.

There is so much more that I could say about Wicked, the musical, but given that so much of my enjoyment came out of not knowing very much about it before going to see it, I do not want to deprive anyone else who reads this of the same pleasure. I will leave you with this one last thought, which was given to me before I saw the musical by someone else who had just seen it: after you see Wicked, you will never be able to see The Wizard of Oz the same way again. I wish the same thing could be said for the novel, but after reading it, I'm just glad that I saw the play first, because otherwise I would have been deprived of an amazing story as a result of its incomprehensible predecessor.

Wicked, by Gregory Maguire

And that was the only reason why I pressed on through the novel long past the time I would have normally put it down: the hope that somewhere out of the mess of complicated language, unlikeable characters, and incomprehensible plot would come some glimmer of the story that I had fallen in love with. Unfortunately, it was nowhere to be found. The musical took the basic premise--tell the story behind the Wicked Witch of the West--and its broadest brushstrokes--character names, the general tone of their relationships to one another, and some of the events in their lives that play a part in their motivations--but other than that, the two stories could not be more different.

In Wicked, the novel, Elphaba, the green-skinned girl who eventually grows up to become the Wicked Witch of the West, is a strange, wholly-unlikeable person. She doesn't know how to relate to anyone, her motivations are never truly made clear, and the only thing that makes her a remotely sympathetic character is the fact that she seems completely oblivious as to how to do anything to make people like her. That would not be enough to completely derail the story--unlikeable characters can often be made sympathetic through the adversity they face and the people that they face them with--except that there is not a single other character in this novel that is any more likable, accessible, or understandable. I am willing to believe that there was some deep political commentary going on within the novel, but the author's descriptive language was so complicated, the character's dialogue so flowery and actions so incomprehensible, and the flow of the plot so random-seeming that it was impossible for me to concentrate on anything other than getting to the next chapter in the hopes that the story would become what I had been expecting it to be. Unfortunately, it never did.

Which is sad, because the story told by Wicked, the musical, is one that I would have loved to read. In the musical, Elphaba is a likable by introverted girl who has been shunned and hated by everyone simply because she was born with green skin and an innate talent for magic that no one had ever seen before. When she goes to Shiz, Oz's university, she is initially treated to levels of ridicule and scorn that any girl, but especially a nerdy, introverted girl, can sympathize with. To make matters worse, she is forced to room with the most popular girl in the school, Galinda, and the two become instant enemies. Over time, though, that enmity transforms into respect, which then blossoms into a friendship between the two young women that is as strong and realistic and relatable as the two characters themselves are. Though they go their separate ways over an event that leads to Elphaba becoming known throughout Oz as the Wicked Witch and Galinda becoming Glinda the Good Witch, they still remain friends, and this colors all of the events that follow the story of The Wizard of Oz in an entirely different light.

There is so much more that I could say about Wicked, the musical, but given that so much of my enjoyment came out of not knowing very much about it before going to see it, I do not want to deprive anyone else who reads this of the same pleasure. I will leave you with this one last thought, which was given to me before I saw the musical by someone else who had just seen it: after you see Wicked, you will never be able to see The Wizard of Oz the same way again. I wish the same thing could be said for the novel, but after reading it, I'm just glad that I saw the play first, because otherwise I would have been deprived of an amazing story as a result of its incomprehensible predecessor.

Wicked, by Gregory Maguire

Sunday, June 3, 2012

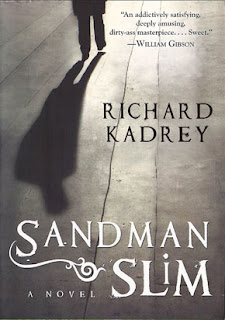

Magic and Demons and Angels... Hell Yeah!: Sandman Slim by Richard Kadrey

I cannot recommend this book enough, and it's rare that I get to say that. It's probably not for everyone--I'm not sure that my mother would like a book about a foul-mouthed, murderous anti-hero whose sole purpose in life is killing the people who were responsible for killing his girlfriend and sending him to Hell for eleven years, for example--but I think the reason why I liked it so much was that if you had told me that the story's protagonist was the man I'd just described, I probably wouldn't have liked it either. But I didn't know anything about the story. All I knew was that it was highly-praised by several websites that share my taste in fiction, and at the time it was free, which is more than enough reason for me to give any book a shot. And boy was I ever glad that I got my hands on this one.

The book's protagonist, Stark, is exactly as described above. As a cocky young man with an incredible talent for magic, he fell in with a group of other magic-users that he thought were his friends, but who all ended up conspiring with the group's de-facto leader, Mason, to send him to Hell. They expected him to stay there and be tortured forever, but eleven years later, upon discovering that Mason has killed the only girl he ever cared about, Stark finds a way out of Hell and proceeds to use his magic powers, the skills and talents he picked up while fighting in Hell's arena, a few on-again, off-again allies, and every other trick he can pull out of his often-destroyed sleeves to turn Los Angeles upside down looking for Mason and all his other former friends, determined to make them suffer his wrath before he kills them. In the process, he manages to piss off angels, demons, Homeland Security, and everyone he tries to reach out to for help, steals more cars and goes through more clothes than you would expect one man in a one-week time-period to be capable of, discovers a lot about himself and the world that he really didn't want to know, and makes a name for himself among the supernaturals of the world (I'll let you guess what that might be...).

This book took me on a much better ride than I had initially expected, because along with not knowing anything about its premise, I also didn't know what genre it was coming from. I was expecting a paranormal fantasy, so, knowing that there are sequels to this book, I was anticipating Stark's revenge to be a long, slow journey hunting down the other members of his former group. This book, though, is actually a paranormal mystery in a wonderfully modern noir style. As a result, the plot moves quickly and takes so many twists and turns that I occasionally felt myself getting mental whiplash while reading it. The story is fast-paced, but rarely confusing, and Richard Kadrey's prose is brilliantly evocative and keeps pace masterfully with the plot. I was hooked from the very first sentence, I can't wait to read his other books, and this is definitely one of those books that I will be coming back to again and again.

Sandman Slim, by Richard Kadrey

(Author's Note: I wish I could say more about this book, but this review is unfortunately being written almost a month after I finished it, and I don't remember much more than that it was amazing. I will likely be re-reading it before going on to the other books in the series, though, and when that happens, if I have more to say that clarifies anything I have said in this review, I will post an update.)

The book's protagonist, Stark, is exactly as described above. As a cocky young man with an incredible talent for magic, he fell in with a group of other magic-users that he thought were his friends, but who all ended up conspiring with the group's de-facto leader, Mason, to send him to Hell. They expected him to stay there and be tortured forever, but eleven years later, upon discovering that Mason has killed the only girl he ever cared about, Stark finds a way out of Hell and proceeds to use his magic powers, the skills and talents he picked up while fighting in Hell's arena, a few on-again, off-again allies, and every other trick he can pull out of his often-destroyed sleeves to turn Los Angeles upside down looking for Mason and all his other former friends, determined to make them suffer his wrath before he kills them. In the process, he manages to piss off angels, demons, Homeland Security, and everyone he tries to reach out to for help, steals more cars and goes through more clothes than you would expect one man in a one-week time-period to be capable of, discovers a lot about himself and the world that he really didn't want to know, and makes a name for himself among the supernaturals of the world (I'll let you guess what that might be...).

This book took me on a much better ride than I had initially expected, because along with not knowing anything about its premise, I also didn't know what genre it was coming from. I was expecting a paranormal fantasy, so, knowing that there are sequels to this book, I was anticipating Stark's revenge to be a long, slow journey hunting down the other members of his former group. This book, though, is actually a paranormal mystery in a wonderfully modern noir style. As a result, the plot moves quickly and takes so many twists and turns that I occasionally felt myself getting mental whiplash while reading it. The story is fast-paced, but rarely confusing, and Richard Kadrey's prose is brilliantly evocative and keeps pace masterfully with the plot. I was hooked from the very first sentence, I can't wait to read his other books, and this is definitely one of those books that I will be coming back to again and again.

Sandman Slim, by Richard Kadrey

(Author's Note: I wish I could say more about this book, but this review is unfortunately being written almost a month after I finished it, and I don't remember much more than that it was amazing. I will likely be re-reading it before going on to the other books in the series, though, and when that happens, if I have more to say that clarifies anything I have said in this review, I will post an update.)

Sunday, April 15, 2012

When the frame is more interesting than the picture...: "I'm Starved for You" by Margaret Atwood

This is a review for a short story, so it will be a short review. I recently read Margaret Atwood's famous novel The Handmaid's Tale for the first time, so when I found out that she had recently released a short story set in another dystopian future, I jumped on it immediately. (That, incidentally, is the number-one reason why I love e-book readers. The fact that I can go from reading about a new novel or story by an author that I like to reading that very novel or story within minutes is the most amazing and wonderful thing that could have ever happened to an avid reader like me. In fact, the reboot of this blog probably would not have happened if it hadn't been for e-books. Yay technology!)

The story itself was a love triangle scenario whose initial twist I actually saw coming (something that never happens) and thereafter failed to hold my interest, but the dystopian society that Atwood wrote to hold the story was fascinating. In a not-so-distant future where the US has been ravaged by crime, joblessness, and prison overcrowding, a corporation has stumbled on the solution to all the country's problems! Using a small town whose only remaining industry after the economic collapse was a massive prison, it decides to run a social experiment that turns the entire town into a prison. It walls the town off, makes it almost entirely self-sustaining, and signs up volunteers from the outside to come and live there. The catch? Half of the population are prisoners and the other half are productive citizens who run the prison and the town, and every month they switch places. In effect, this company has decided that the best way to deal with the growing prison population is to create communities in which everyone--criminals and normal citizens alike--are treated the same, like criminals half of the time and like ordinary citizens the other half.

The idea is crazy, but it makes for an interesting thought experiment around the freedoms that people will give up in order to ensure their personal security and futures. If the violence, the degradation, and the personal danger could be removed from the prison experience, how many people do you think would be willing to spend half of their lives wearing an orange jumpsuit and sleeping in a cell for a chance at a stable job, a roof over their heads, and a place as a productive member of a community the other half of the time? More importantly, what do we need to do as a society to ensure that no one will ever be asked to make that choice? What can we be doing better for the people who would say yes to giving up their basic freedoms for the chance at a normal, stable, middle-class lifestyle?

Just something to think about...

"I'm Starved for You", by Margaret Atwood

The story itself was a love triangle scenario whose initial twist I actually saw coming (something that never happens) and thereafter failed to hold my interest, but the dystopian society that Atwood wrote to hold the story was fascinating. In a not-so-distant future where the US has been ravaged by crime, joblessness, and prison overcrowding, a corporation has stumbled on the solution to all the country's problems! Using a small town whose only remaining industry after the economic collapse was a massive prison, it decides to run a social experiment that turns the entire town into a prison. It walls the town off, makes it almost entirely self-sustaining, and signs up volunteers from the outside to come and live there. The catch? Half of the population are prisoners and the other half are productive citizens who run the prison and the town, and every month they switch places. In effect, this company has decided that the best way to deal with the growing prison population is to create communities in which everyone--criminals and normal citizens alike--are treated the same, like criminals half of the time and like ordinary citizens the other half.

The idea is crazy, but it makes for an interesting thought experiment around the freedoms that people will give up in order to ensure their personal security and futures. If the violence, the degradation, and the personal danger could be removed from the prison experience, how many people do you think would be willing to spend half of their lives wearing an orange jumpsuit and sleeping in a cell for a chance at a stable job, a roof over their heads, and a place as a productive member of a community the other half of the time? More importantly, what do we need to do as a society to ensure that no one will ever be asked to make that choice? What can we be doing better for the people who would say yes to giving up their basic freedoms for the chance at a normal, stable, middle-class lifestyle?

Just something to think about...

"I'm Starved for You", by Margaret Atwood

What happens to gods when people stop believing in them?: American Gods by Neil Gaiman

This book is a hard one for me to review, partly because, what with one thing and another, it took me a lot longer to read than most books normally do, and partly because I have always had a hard time deciding whether I like it or not. It is one of those rare books that I have trouble remembering much about--no matter how many times I have read it, only certain elements of the story, most incidental to the plot, ever stick with me, and they carry with them no context by which I can later evaluate how the overall narrative made me think or feel. Given my extensive memory, especially for books I have read, this is a rare occurrence, and it almost says more about how I feel about the story itself than a review of the book itself could.

I believe that most of the blame for the story's lack of a "sticky" plot falls on its main character, Shadow. Shadow is an ex-con who gets out of prison a few days early in order to attend his wife's funeral. While traveling home, he meets a man named Wednesday, who turns out to be the Norse god Odin, and agrees to work for him. In the process of traveling with Wednesday and working for him, Shadow meets a number of other gods, old and new, and finds out that they are at war with one another. Shadow helps bring them all together for the war, has a few crazy adventures himself, and ultimately learns a lot about his own past and uses his newfound position and knowledge to bring the conflict to a somewhat satisfying end.

I love this book for its portrayal of the gods, its stories of their histories, its explanations of their motivations, and, especially, its reasoning of how they all came to America in the first place and why they are so unsettled here, in their secondary home, when they were so stable in their countries of origin. Unfortunately, Shadow lacks everything that the gods have when it comes to characterization, personality, and relatability. Over the course of the story, it becomes clear that his expressionless, monosyllabic woodenness is his character, but there is no doubt in my mind that it is also the reason why I find the overarching plot of this novel to be so entirely forgettable, even though there are elements of it that I can never seem to forget.

That doesn't make it a bad novel, though. Neil Gaiman is one of my favorite authors specifically for his unconventional takes on classic stories and story tropes, and his portrayal here of the gods of the myths and legends that I grew up reading speaks to the heart of my love for the stories inherent in all mythologies and religions. That the gods of those old religions, upon being invoked by their followers when they came to this new world, would manifest here in America and be shaped by its unique history and culture is a fascinating thought, and to see them warring against the modern gods of technology, industry, and capitalism, neither side wanting to recognize that they are not in control of their own rise to power or obsolescence, makes for biting social commentary, even more-so now than it did ten years ago when this book was first printed. And it is that story--the story of the gods and their fight for relevance in a country and a world that so easily casts one idea aside for another--that brings me back to this book over and over again. It may be that writing this review cements the story enough in my mind that I won't forget it this time around, but I don't think that will stop me from picking it up in another five years, or ten, or twenty, because even though the need to believe in the gods of old has been lost, their stories and the history that they represent will always shape our present and our future.

Two random notes:

- One of the pivotal scenes early in the book takes place at a somewhat-well-known roadside attraction called the House on the Rock. Because I am a fan of extremely bizarre and random coincidences, I am going to use that fact as an excuse to share with you my absolute favorite podcast ever, because--completely coincidentally--the day after I finished reading the section of the book that talked about the House on the Rock, that podcast had an awesome verbal walkthrough of the bizarre attraction. As a result, the House on the Rock is now on my list of "Things to See Some Day," and if you want to hear that bizarre description for yourself, go to the Geologic Podcast website, scroll down to episode #258 (or just follow the links), and listen to the first fifteen minutes or so of the show.

- The version of American Gods that I am reviewing here is the Tenth Anniversary Edition, Author's Preferred Text. I am not sure what was changed within this edition from prior versions--though I doubt it was anything significant--but if you are planning on reading this book based on my recommendation, I definitely recommend this edition if only for the introduction by the author, which will give you some really good backstory on him and on where his ideas for the book came from. Enjoy!

American Gods, the Tenth Anniversary Edition, by Neil Gaiman

I believe that most of the blame for the story's lack of a "sticky" plot falls on its main character, Shadow. Shadow is an ex-con who gets out of prison a few days early in order to attend his wife's funeral. While traveling home, he meets a man named Wednesday, who turns out to be the Norse god Odin, and agrees to work for him. In the process of traveling with Wednesday and working for him, Shadow meets a number of other gods, old and new, and finds out that they are at war with one another. Shadow helps bring them all together for the war, has a few crazy adventures himself, and ultimately learns a lot about his own past and uses his newfound position and knowledge to bring the conflict to a somewhat satisfying end.

I love this book for its portrayal of the gods, its stories of their histories, its explanations of their motivations, and, especially, its reasoning of how they all came to America in the first place and why they are so unsettled here, in their secondary home, when they were so stable in their countries of origin. Unfortunately, Shadow lacks everything that the gods have when it comes to characterization, personality, and relatability. Over the course of the story, it becomes clear that his expressionless, monosyllabic woodenness is his character, but there is no doubt in my mind that it is also the reason why I find the overarching plot of this novel to be so entirely forgettable, even though there are elements of it that I can never seem to forget.

That doesn't make it a bad novel, though. Neil Gaiman is one of my favorite authors specifically for his unconventional takes on classic stories and story tropes, and his portrayal here of the gods of the myths and legends that I grew up reading speaks to the heart of my love for the stories inherent in all mythologies and religions. That the gods of those old religions, upon being invoked by their followers when they came to this new world, would manifest here in America and be shaped by its unique history and culture is a fascinating thought, and to see them warring against the modern gods of technology, industry, and capitalism, neither side wanting to recognize that they are not in control of their own rise to power or obsolescence, makes for biting social commentary, even more-so now than it did ten years ago when this book was first printed. And it is that story--the story of the gods and their fight for relevance in a country and a world that so easily casts one idea aside for another--that brings me back to this book over and over again. It may be that writing this review cements the story enough in my mind that I won't forget it this time around, but I don't think that will stop me from picking it up in another five years, or ten, or twenty, because even though the need to believe in the gods of old has been lost, their stories and the history that they represent will always shape our present and our future.

Two random notes:

- One of the pivotal scenes early in the book takes place at a somewhat-well-known roadside attraction called the House on the Rock. Because I am a fan of extremely bizarre and random coincidences, I am going to use that fact as an excuse to share with you my absolute favorite podcast ever, because--completely coincidentally--the day after I finished reading the section of the book that talked about the House on the Rock, that podcast had an awesome verbal walkthrough of the bizarre attraction. As a result, the House on the Rock is now on my list of "Things to See Some Day," and if you want to hear that bizarre description for yourself, go to the Geologic Podcast website, scroll down to episode #258 (or just follow the links), and listen to the first fifteen minutes or so of the show.

- The version of American Gods that I am reviewing here is the Tenth Anniversary Edition, Author's Preferred Text. I am not sure what was changed within this edition from prior versions--though I doubt it was anything significant--but if you are planning on reading this book based on my recommendation, I definitely recommend this edition if only for the introduction by the author, which will give you some really good backstory on him and on where his ideas for the book came from. Enjoy!

American Gods, the Tenth Anniversary Edition, by Neil Gaiman

Sunday, March 25, 2012

The Hunger Games: The Movie Review

So, since I did reviews of all the books, it seems only right that I should do a review of the movie as well. The short version: It was amazing. It was a very good movie that stuck closely to the novel both in story and in form, used the visual medium that movies work in to enhance the story and express the first-person, emotionally-driven narrative that makes the book so gripping to great effect, and managed to make a good movie that even people who have not read the books will like.

What impressed me most about the movie was the way they used the camera to bring across Katniss's thoughts and emotions throughout the film. In the book, the story is told entirely from her perspective, so you know what she thinks and feels about everything. In the movies, however, it is much more difficult to get that kind of personal narrative across to the audience, and I will be forever grateful that this movie didn't take either of the two cheesy ways out--voice-over narration or having the character say everything she is thinking. In fact, Katniss says very little, but close-ups of her reactions to events, tight camera angles that follow her and her alone, and a few extremely effective flashback scenes let you know what's going on inside her head without bringing you out of the story.

I was also pleased with the scenes where the film chose to diverge from the narrative of the book. Scenes showing some of the workings behind the Games, conversations between the people in charge of the events, and reaction shots from the Capital and some of the Districts while the Games are going on bring across a bit of why things are the way they are subtly and tastefully. In particular, the contrast shots between the gaudy excesses and the technological marvel that is the Capital and the shots of District 12--which looks like an Appalachian coal-mining town straight out of the Depression--easily sets the stage for the rebellion that is hinted at as being inevitable, despite the fact that the Hunger Games was specifically designed to make sure that no such rebellion ever happened again.

The only place where the movie seems to fall a bit short is in its deeper narrative. I can't speak to this myself, but I saw the movie with someone who had not read the books, and he said at the end that he was drawn out of the story a bit by a lack of understanding of things that are already known to anyone who has read the books. It didn't take away from his enjoyment of the movie, and it made him curious about the full story, but looking back on it from that perspective I can see a few places where attempts to keep from narrating everything out in too obvious a manner made some explanations so subtle that they can go right over the heads of people who didn't know what they meant in the first place.

All in all, though, the movie was both an amazing adaptation of the book and a very good movie on its own, at least in my opinion. It was visually stunning, emotionally gripping, and did not feel at all like most movie adaptations of good books that I have seen in recent years have felt--which only made it that much better. I feel that it is a movie that can stand on its own cinematic merits as well as on the fact that it is based on a hugely-popular book, and I can only hope that future filmmakers learn from its success and that we get more good movie adaptations like it in the future.

Since I am not as good at objectively watching movies than I am at reading books, especially after only one viewing, I will leave you with a few links to reviews of the movie from sites that I follow with similar tastes in movies to mine.

io9's Review

Pajiba's Review

MovieBob's Review

What impressed me most about the movie was the way they used the camera to bring across Katniss's thoughts and emotions throughout the film. In the book, the story is told entirely from her perspective, so you know what she thinks and feels about everything. In the movies, however, it is much more difficult to get that kind of personal narrative across to the audience, and I will be forever grateful that this movie didn't take either of the two cheesy ways out--voice-over narration or having the character say everything she is thinking. In fact, Katniss says very little, but close-ups of her reactions to events, tight camera angles that follow her and her alone, and a few extremely effective flashback scenes let you know what's going on inside her head without bringing you out of the story.

I was also pleased with the scenes where the film chose to diverge from the narrative of the book. Scenes showing some of the workings behind the Games, conversations between the people in charge of the events, and reaction shots from the Capital and some of the Districts while the Games are going on bring across a bit of why things are the way they are subtly and tastefully. In particular, the contrast shots between the gaudy excesses and the technological marvel that is the Capital and the shots of District 12--which looks like an Appalachian coal-mining town straight out of the Depression--easily sets the stage for the rebellion that is hinted at as being inevitable, despite the fact that the Hunger Games was specifically designed to make sure that no such rebellion ever happened again.

The only place where the movie seems to fall a bit short is in its deeper narrative. I can't speak to this myself, but I saw the movie with someone who had not read the books, and he said at the end that he was drawn out of the story a bit by a lack of understanding of things that are already known to anyone who has read the books. It didn't take away from his enjoyment of the movie, and it made him curious about the full story, but looking back on it from that perspective I can see a few places where attempts to keep from narrating everything out in too obvious a manner made some explanations so subtle that they can go right over the heads of people who didn't know what they meant in the first place.

All in all, though, the movie was both an amazing adaptation of the book and a very good movie on its own, at least in my opinion. It was visually stunning, emotionally gripping, and did not feel at all like most movie adaptations of good books that I have seen in recent years have felt--which only made it that much better. I feel that it is a movie that can stand on its own cinematic merits as well as on the fact that it is based on a hugely-popular book, and I can only hope that future filmmakers learn from its success and that we get more good movie adaptations like it in the future.

Since I am not as good at objectively watching movies than I am at reading books, especially after only one viewing, I will leave you with a few links to reviews of the movie from sites that I follow with similar tastes in movies to mine.

io9's Review

Pajiba's Review

MovieBob's Review

Sunday, February 26, 2012

An Outsider No Matter Where He Goes: The Cloud Roads by Martha Wells

This book came to me unexpectedly thanks to a friend's recommendation and the fact that I love things that are free. Whenever I hear about a book recommendation from someone that is free for my Kindle, I will get it just because I love having books--the six overflowing bookcases in my apartment will attest to this as well--but I was pleasantly surprised at what a good fantasy novel The Cloud Roads turned out to be.

Moon, the story's main character, is alone in the world. He was orphaned as a child, and though the many cities and towns he has traveled to throughout his life are populated by intelligent species of humanoids that look somewhat like him, he has never found a place where he belongs, and he has no idea where or even what race of people he comes from. The reason why he doesn't fit in is because he can shift from looking like a 'groundling' into a large, dangerous-looking flying creature, and the problem with that is that the world is plagued by a race of violent, warlike creatures called the Fell and, though he is not one of them, his flying form looks remarkably similar to that of the Fell. When the story starts, Moon has been living with a settlement of peaceful groundlings for several years and finally starting to feel like he belongs there, but one night, someone sees him shift into his flying form, believes he is a Fell, and the entire village turns against him. They drug him and stake him out to be eaten by wild creatures, but he is rescued by a flying monster that he soon discovers is another one of his people--a Raksura.

This Raksura is named Stone, and he is the consort to the queen of a colony of Raksura who are in desperate trouble. A complete explanation of their physical and social heirarchy is best left to a reading of the book, but, to put it simply, they have both fertile and infertile males and females and their biology determines their place within the colony. Stone's colony is in trouble because it has been unable to produce consorts, the only type of Raksuran who can mate with Raksuran queens, and Moon just happens to be one of those, so Stone convinces Moon to come back to his colony, where he will finally be among his own people again.

Of course, Moon's problems don't end there. The colony's population problems stem from trouble with the Fell, he is not easily accepted into their home, and he has to find a way to save the colony even though many of its people, including its queen, hate him for being an outsider who is ignorant of their ways. All of this conflict creates an excellent story that made the book hard to put down. I am not well-versed in all of the different styles of fantasy, so this was a new and intriguing read for me in more ways than one, and I plan on looking for more books by this author and in this fantasy style in the future.

This book also got me thinking about a trope in fantasy and science fiction that was recently brought to my attention--that of telling the story from the point of view of the naive outsider. It is such a common and necessary trope when introducing readers to a world outside of their sphere of knowledge that it can easily go unnoticed. In this story, the trope was more obvious than most, but only because Moon's outsider status was a stigma both in the world where he didn't belong and in the world where he did. The style has its strengths and weaknesses--it makes a strange world populated by non-humans much more accessible and easier to visualize and accept without being pulled out of the story by long descriptions, but it also means that some of the character's personal story can be sacrificed for the sake of his new experiences-- but recognizing this storytelling style and being able to analyze its strengths and weaknesses within one book whose plot was tailor-made for it has already opened my eyes to its possibilities in my own writing, which is what I am striving for first and foremost in reading books with a critical eye.